Deduplicating and cleaning large data sets (aka "entity resolution") is a hard problem that comes up all the time. There are tools that work at scale, and there are tools that are intelligent, but very few do both. This post covers the practical approach we've landed on after working through a lot of messy real-world data: a funnel that starts with fast string matching, graduates to embeddings, and only calls an LLM for the hard cases.

Real-world deduplication comes with a variety of challenges:

Scale. Often, datasets will have thousands or millions of records.

Entries vary. Abbreviations ("NYC" vs "New York City"), typos ("Jonh Smith"), missing values, inconsistent formatting. Two records can refer to the same entity while sharing almost no character-level similarity.

Equivalence depends on context. Often you need context to determine equivalence. For example, if a person married and changed their name, there is no way to determine whether they are the same person. If they still have the same address and phone number, that's strong evidence. Going further, context can also dictate whether something should be treated as a duplicate or not. A product with the same name but different stock keeping unit (SKU, a unique identifier for a product) might be a variant or a duplicate, depending on your use case.

World knowledge. Some duplicates require actual intelligence and knowledge of the world to detect. For example, consider a company that changed their name but is still the same legal entity. Or consider nicknames, like "Big Blue" as a nickname for "IBM".

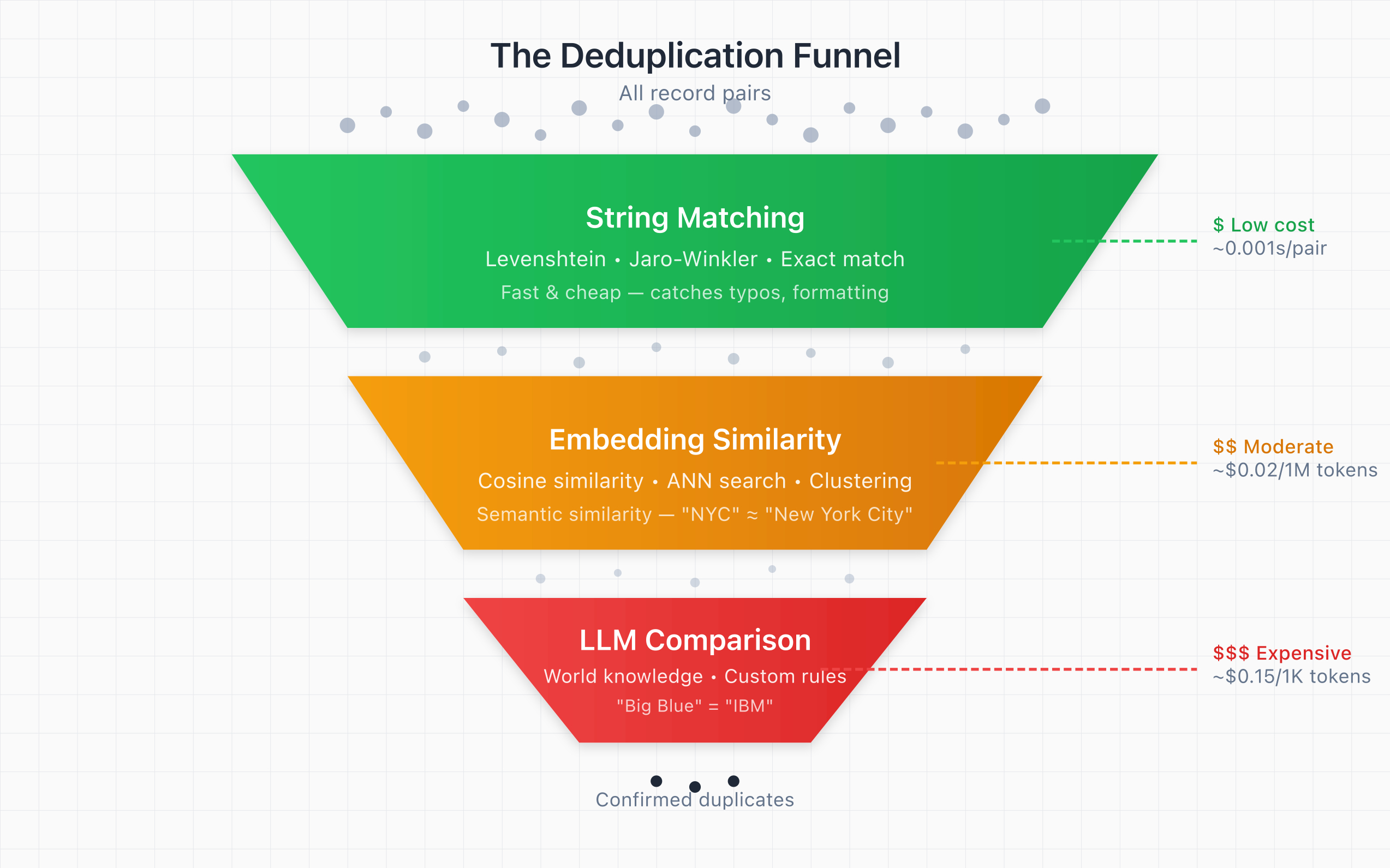

The requirement to deal with all of these makes it hard to balance cost, runtime, and accuracy in terms of false positives and false negatives. Developing a system that can deduplicate complicated data at scale will usually be funnel-shaped. The idea is you start with fast, simple, and cheap solutions, and then gradually add more intelligence and complexity as needed.

Here is an illustration:

Three Components of The Deduplication Funnel

There are roughly three ways to detect duplicates, each with different trade-offs.

Generally speaking, a good idea is to try all of these exactly in that order (though you may be able to stop early if your task is already solved).

String Matching

The basic idea is comparing whether two strings are identical or at least similar, according to a variety of metrics. String matching is fast, cheap, and can be surprisingly powerful and effective, solving the majority of deduplication problems.

The simplest starting point is exact matching — just check if two strings are identical. Most of the time, this will not catch a lot of duplicates, but it's fast and worth doing first to handle the easy cases.

When exact matching fails (which it usually does), you need fuzzy matching. Essentially, you take two strings and you compute a similarity score between them. Then you pick a threshold and call something a duplicate if the score between two strings is above the threshold and a non-duplicate otherwise.

In practice, thresholds are dataset-specific. A reliable way to pick them is to label a small sample of pairs (100–300 is often enough), look at the score distributions for true matches vs non-matches, and then choose a cutoff based on looking at the plot of false positives vs false negatives.

The two most important algorithms to know are:

The Levenshtein distance. Counts the minimum number of single-character edits (insertions, deletions, substitutions) needed to transform one string into another. "John" → "Jonh" = 2 edits. Lower distance = more similar. Usually it makes sense to transform this distance into a score between 0 and 1, where 1 means the strings are identical.

The Jaro-Winkler similarity. An alogithm designed for short strings like names. It considers matching characters, transpositions, and gives a bonus for matching prefixes. It's particularly good for typos because transpositions ("Jonh" vs "John") are penalized less than insertions/deletions.

import textdistance

# Levenshtein: normalized similarity (0 to 1)

textdistance.levenshtein.normalized_similarity("John Smith", "Jonh Smith") # 0.9

# Jaro-Winkler: designed for names

textdistance.jaro_winkler("John Smith", "Jonh Smith") # 0.96

Useful Libraries in Python

- textdistance: Provides 30+ string distance algorithms in a unified interface.

- rapidfuzz: Fast implementation in C++ of common fuzzy matching algorithms. Better than textdistance for larger datasets.

- Splink: Nice package that does some clever things related to feature frequency. For example, if "Smith" appears in 20% of your records but "Xydfakjhzzy" appears only twice, then two entries that both have "Xydfakjhzzy" are more likely to be identical than two entries that share "Smith".

Preprocessing

Fuzzy matching works better on cleaned text. Common preprocessing includes

- Lowercase everything

- Normalize whitespace

- Remove or normalize punctuation

Sometimes, though, you have to be careful when stripping whitespace and punctuation as you risk creating false matches. Look at this example:

# entirely stripping both whitespace and punctuation

# can create false positives:

"56 5th Avenue" → "565THAVENUE"

"5, 65th Avenue" → "565THAVENUE"

# replacing punctuation with spaces

# (or some standardized character) may work better:

"56 5th Avenue" → "56 5th avenue"

"5, 65th Avenue" → "5 65th avenue"

Balancing False Positives and False Negatives

With string matching, you will inevitably end up with false positives and false negatives.

One improvement you can make over the simple approach suggested above is choosing several algorithms and combining the results. Usually, you get more robust results if you compute different scores, choose a different threshold for each score, and then call something a duplicate if at least some portion of the scores are above their respective thresholds.

Embedding-Based Similarity

String matching fails on semantic equivalence (things that mean the same thing, but look very different when looking at the strings, e.g. "NYC" and "Big Apple"). Embeddings can often handle these well.

Embeddings are vector representations of the text, created by models that have an actual understanding of the meaning of the text. Essentially, every string becomes an arrow in a multidimensional space. You can then measure the similarity between the vectors by computing the cosine similarity, i.e. by looking at the angle between the arrows. The closer the angle, the more similar the two items. With embeddings, you have a good chance of catching that "Dr. John Smith" and "Smith, John (MD)" are the same person.

Here is an example in code:

from openai import OpenAI

import numpy as np

client = OpenAI()

def get_embedding(text: str) -> list[float]:

response = client.embeddings.create(

input=text,

model="text-embedding-3-small"

)

return response.data[0].embedding

def cosine_similarity(a: list[float], b: list[float]) -> float:

a, b = np.array(a), np.array(b)

return np.dot(a, b) / (np.linalg.norm(a) * np.linalg.norm(b))

# String matching would score these as quite dissimilar

emb1 = get_embedding("NYC")

emb2 = get_embedding("New York City")

print(cosine_similarity(emb1, emb2))

If you don't have an OpenAI API key, you can also try out this free alternative:

# works without an API key

from sentence_transformers import SentenceTransformer

model = SentenceTransformer('all-MiniLM-L6-v2')

embeddings = model.encode(["NYC", "New York City"])

Similarity vs. Equivalence

There is one potential gotcha: embeddings measure relatedness, not equivalence. For example, Apple Inc. and Microsoft Corporation are related but not duplicates, while IBM and International Business Machines are duplicates. Similarly, models might trip over other non-obvious cases like a rename/rebrand (e.g., "Facebook" vs "Meta Platforms"). In most cases, this should still work, but there may be cases where a purely embeddings-based approach will break down.

Scaling with Approximate Nearest Neighbor Search

Before reaching for ANN, consider whether simple blocking can reduce your comparison space. Blocking means grouping records by a shared attribute - first letter of last name, zip code, company domain — and only comparing within blocks. This alone can take you from O(n²) to something manageable. ANN is the next step when your blocks are still too large or when your blocking key itself has variations.

Comparing every pair of embeddings can also be expensive. A technique like Approximate Nearest Neighbor (ANN) identification allows you to cluster items first before running pairwise comparisons. Some common libraries include

The approach of ANN is to cluster closely-related items together. Once you've clustered items together, you can then do pairwise comparisons between items within each cluster. I won't go into details, but you can find a lot of examples online if it becomes necessary for your data.

The downside, of course, is the risk of creating false negatives. If two items end up in different clusters, they may never even be considered for pairwise comparison.

Miscellaneous Embedding Tips

- Concatenate the contents of relevant columns into a single string.

- However, make sure to remove noise first and only embed the columns you actually need.

- BatchAPI calls.

LLM-Based Comparison

Instead of computing similarity scores, you ask a language model directly: "Are these two records referring to the same entity?" That unlocks a lot of intelligence, but also is expensive.

from openai import OpenAI

client = OpenAI()

def are_duplicates(record1: str, record2: str, equivalence_relation: str) -> bool:

response = client.chat.completions.create(

model="gpt-5",

messages=[{

"role": "user",

"content": f"""Determine if these two records refer to the same entity.

Equivalence relation: {equivalence_relation}

Record 1: {record1}

Record 2: {record2}

Answer only "yes" or "no"."""

}],

max_tokens=10,

temperature=0,

)

return response.choices[0].message.content.strip().lower() == "yes"

The great advantage of LLMs is that you can define what "duplicate" means for your specific use case. For example, consider a person who has married and changed their last name. You can tell an LLM to count two people as duplicates if the first name, the address, and the phone number are the same. Or you can leave the judgment to the LLM. For example, an LLM should be able to realize that [email protected] and [email protected] probably belong to the same person.

Structured output

In the example above, I didn't ask an LLM to produce any structured output. Usually though, that's exactly what you should do. Defining a schema and validating the model output against it makes sure you get consistent responses.

You should also include a reasoning field and have the LLM return its rationale. That is useful for debugging and understanding LLM outputs.

Batching

Again, you should probably batch comparisons to decrease the total number of API calls (for a batch size of N, you only have to do one API call instead of N×(N-1)/2 calls).

In addition, the LLM seeing all items together can help with consistency. But be careful, accuracy can degrade with very large batches. We've found 20–30 items per batch works well.

Putting it all together

The ideal outcome for entity resolution would be "LLM-level accuracy without LLM-level cost". Most likely, you won't be able to achieve that. There is a lot of optimization you can do, but at some point, you have to pick your poison among cost/runtime, and accuracy (false positives/negatives).

For most datasets, I would recommend the funnel-shaped approach mentioned above:

- Applying string matching first, filtering out duplicates

- Embedding your records and clustering them using ANN

- Asking LLMs to verify the cases that ranked in the probably-but-not-definitely-a-match category in terms of string similarity and cosine similarity.

What the funnel exactly looks like will depend on your specific data and task. We've packaged some of this into an open-source tool called everyrow.